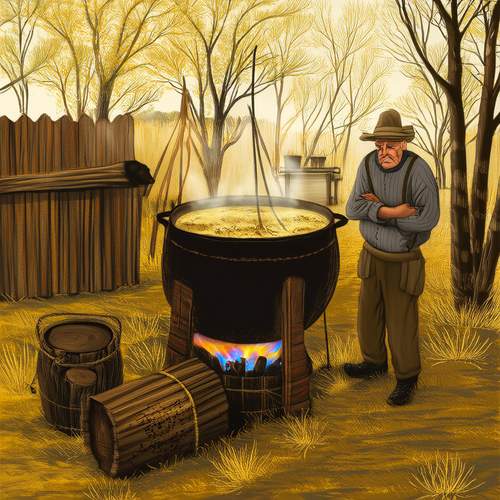

The sweet, golden hues of Diwali are not just confined to the flickering diyas and vibrant rangolis. They spill over into the kitchen, where pots of simmering sugar syrup form the heart of countless Indian sweets. This viscous, shimmering liquid is more than just a sweetener—it’s an alchemical ingredient that transforms humble flour, nuts, and dairy into celebratory delicacies. The art of preparing sugar syrup for Indian mithai is a dance of precision, tradition, and regional flair, passed down through generations with the same reverence as family heirlooms.

The Science and Soul of Syrup

At its core, sugar syrup is deceptively simple—just sugar and water heated together. But the magic lies in the stages it passes through as temperature climbs. The "thread" stages (ek or do tar in Hindi) are crucial. A single-thread syrup, when pressed between thumb and forefinger, forms one delicate strand—perfect for gulab jamun. A two-thread syrup, slightly thicker, is ideal for jalebi or sohan papdi. Miss the window, and the texture falters; boiled too long, the syrup crystallizes into a grainy disappointment. Experienced cooks often test by eye and touch, reading the bubbles’ size or how the syrup drips from a spoon.

Regional variations abound. In Bengal, a light cardamom-infused syrup bathes spongy rasgullas, while Gujarati mohanthal demands syrup cooked to the elusive "full pearl" stage. South India’s mysore pak requires sugar boiled to the hard-ball stage before being frenetically mixed with ghee and gram flour. The syrup’s temperature determines whether a sweet will be soft and juicy or crumbly and dense—a difference that can make or break a Diwali sweet box.

Beyond Sweetness: Syrup as Cultural Code

Diwali syrup carries symbolism beyond culinary function. The clarity of the syrup reflects purity—cloudy syrup is considered inauspicious for festive sweets. Many households still use copper pots for boiling, believing it enhances both flavor and ritual significance. The first batch of syrup is often offered to the gods before being used, especially when making prasadam like til ke laddoo or motichoor.

Certain communities have signature techniques. Sindhi families might add a splash of rosewater to their syrup for khoya-based treats, while Punjabi halwais swear by boiling syrup with milk solids to prevent crystallization. In Odisha, a pinch of edible camphor in the syrup for chenna poda lends an aromatic depth. These nuances speak to India’s gastronomic diversity—where even something as universal as sugar syrup carries distinct regional fingerprints.

The Forgotten Art of Patience

Modern shortcuts—corn syrup, glucose powder, pre-made mixes—have crept into some kitchens, but traditionalists maintain that Diwali sweets demand slow-cooked syrup. The process can’t be rushed; impurities must be skimmed, the heat monitored. Some recipes, like for 24-carat gold leaf-adorned paneer barfi, require the syrup to rest overnight before use. This temporal investment mirrors the festival’s spirit—a slowing down, a deliberate savoring.

Old cookbooks speak of "chaashni," where sugar is dissolved cold before heating—a method believed to yield superior clarity. Others describe "pak" systems with eight precise stages, each with Sanskrit names like "plava" or "pichka." While few home cooks today memorize these terms, their influence persists in the instinctive knowledge of when syrup has reached its ideal state.

Syrup Troubleshooting: A Grandmother’s Wisdom

Even experts face syrup mishaps—cloudiness, graininess, or incorrect thickness. Traditional remedies abound: a few drops of lemon juice to prevent crystallization, a charcoal piece dipped in to remove impurities, or a handful of crushed betel nuts to clarify cloudy syrup. Some advise stirring only with wooden spoons to avoid metallic flavors. These kitchen hacks, often dismissed as superstition, frequently have scientific basis—the acidity in lemon juice inverts sucrose molecules, for instance.

Weather plays unexpected roles. Humid monsoon Diwalis may require adjusting syrup stages, as moisture affects sugar crystallization. High altitudes demand modified cooking times. The truly skilled adjust instinctively—a talent honed over decades of festival seasons, where sweet-making is as much about environmental awareness as recipe fidelity.

The Future of Festive Syrups

Health consciousness has spurred innovation. Jaggery syrup now replaces sugar in some versions of laddoos, while date syrup sweetens "sugar-free" kalakand. Vegan adaptations use agar syrup for dairy-free sandesh. Yet purists argue that Diwali, as a celebration, warrants indulgence in traditional recipes—that the festival’s essence lies partly in these unabashedly rich, syrup-drenched creations.

What remains unchanged is syrup’s role as culinary adhesive—binding not just ingredients, but generations. As children dip their fingers into pots of warm syrup (despite admonishments), as newlyweds prepare their first Diwali sweets under elders’ guidance, the thread stages of sugar become life stages—measured not just by temperature, but by memories in the making.

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025