The sizzle of beef over glowing embers, the smoky aroma wafting through warm summer air—this is the essence of an Argentine Christmas. While the holiday season in the Northern Hemisphere is synonymous with snow-laden pines and mulled wine, in Argentina, December marks the height of summer, and the asado (barbecue) takes center stage. But achieving the perfect doneness for Christmas asado isn’t just a matter of throwing meat on a grill; it’s a cultural ritual, a test of patience, and an art form passed down through generations.

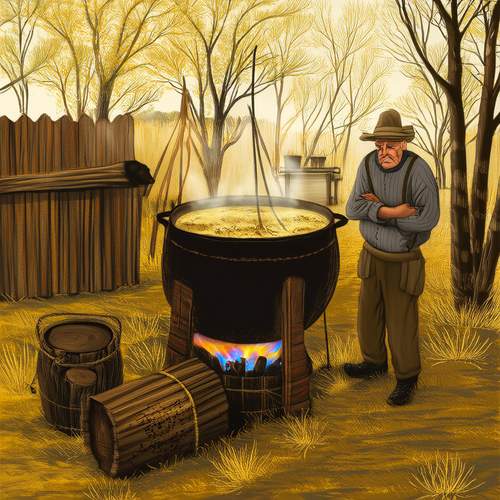

Argentine asado masters, or asadores, approach fire management with near-religious reverence. Unlike the high-heat searing common in American barbecues, Argentine tradition favors slow cooking over hardwood coals, often from quebracho or mesquite. The fire is built separately in a fogon (fire pit) before being carefully transferred beneath the grill grate, ensuring an even, radiant heat. For Christmas asado, where cuts like vacío (flank steak), entraña (skirt steak), and costillas (ribs) dominate, the coals should glow deep red without visible flames—a stage called "punto justo" (the perfect point). This prevents charring while allowing fat to render slowly, basting the meat from within.

Timing is everything. A typical Christmas asado might stretch over four to six hours, with the asador adjusting the coal bed and meat positions like a conductor leading an orchestra. Thicker cuts like bife de chorizo (sirloin strip) are placed farther from the heat, while thinner cuts like mollejas (sweetbreads) get a quick, intense exposure. The true test comes when slicing: Argentine preferences lean toward "jugoso" (juicy medium-rare) for most cuts, with a blushing pink center and crispy, caramelized exterior. At Christmas gatherings, you’ll often hear debates about whether the asador pulled the meat off "un minuto tarde" (a minute too late) or if the doneness is "como lo hace mi abuelo" (just like my grandfather makes it).

What sets Christmas asado apart is its ceremonial pacing. Unlike hurried holiday meals elsewhere, Argentine families savor the process. The meal begins with lighter fare—empanadas, provoleta (grilled provolone)—while the main cuts rest under cloth to redistribute juices. When the meat finally arrives, it’s accompanied by chimichurri made with summer’s freshest herbs, a nod to the season. The fire’s residual heat often toasts pan de campo (country bread) for scraping up every last bit of flavor—a humble yet sacred conclusion to the feast.

In Argentina, Christmas asado isn’t merely cooking; it’s a language of coals and patience, where the fire’s whispers dictate the rhythm of celebration. The perfect doneness isn’t measured with thermometers but by the asador’s instinct, the family’s laughter, and the long shadows of a summer evening—proof that some traditions are best felt, not timed.

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025